I was speaking to a young friend of mine and after a while, it became clear that he had poor grasp of the women’s suffrage movement. Despite his being very well educated, he had a conflated, rosy, piecemeal ‘history’ and development of the feminist movement. One such error was that he had never heard of the Suffragists.

It is now very difficult to talk about ideologies and politics without having a clear understanding of history, not just ancient but also recent and current. For his benefit, and now yours I hope, here is the quick history of the suffragist movement he lacked.

Historical Context

1265 – Elected Members of Parliament

Hundreds of years ago, the only voice that mattered was the King… until the Magna Carta opened the decision making process up to the barons, and Parliament was formed. The members of this Parliament were chosen by the King until 1265 when Members of Parliament started to be elected from the various counties.

1432 – The Knights of the Shire Act

At this time, it was an incredibly small number of people who were able to elect these representatives, who were referred to as the “Knights of the Shire”. The Knights of the Shire Act in 1432 was the first parliamentary legislation to establish who was enfranchised to vote for the members: The act gave the right to vote to “Forty Shilling Freeholders”, meaning that only owners of real property who paid taxes to the Crown of at least 40 shillings per year. This remained the status quo for another 400 years.

1642 – 1651 Civil War

During the Civil War the Levellers, serving as soldiers in the Parliamentary Army, argued for (nearly) universal male suffrage, but their officers defended limiting the vote on the grounds that only people who had a stake in society could be trusted to take part in politics. And by having a stake, they meant owning some part of it… Male and Female. There were 140 MPs represented Rotten Boroughsi. That is 140 out of 658 Members of Parliament. Fifty of those boroughs had fewer than fifty voters. Meanwhile, major industrial cities like Leeds, Birmingham, and Manchester had no MPsii at all.

What was a Rotten Borough like? Gatton, in Surrey, had twenty voters when the monarchy was restored (in 1660), and a hundred years later it was down to two. Old Sarumiii had one farmhouse, some fields, and a lot of sheep. Both sent MPs to parliament. The former port of Dunwich had crumbled into the sea and only 32 people were left above the water line. It didn’t just send one MP to parliament but two. This was how both women as well as men had the vote, because of the complex assortment of “people with property/having a stake in society.”

1780 – Corruption in the System

In England and Wales, about 214,000 peopleiv had the right to vote. That was less than 3% of the total population. In Scotland, the electorate’s even smaller. Pressure to change the system was growing: the middle class was getting larger and richer and as such, elections were becoming more corrupt. People in power gradually began to acknowledge the need for reform, and the Rotten Boroughs were high on the list of changes that needed to be made. But that was some people in power… not all of them.

1819 – Peterloo Massacre

In 1819, a public meeting calling for universal manhood suffrage was attacked, and eleven people were killed. It became known as the Peterloo Massacre. In 1830 the Whigs beat the Tories and passed their reform bill in 1831, but it was defeated by the Tories in the Lords. Because of this, riots broke out in London, Birmingham, Derby, Nottingham, Leicester, Bristol, and other places. In Bristol, people set fire to public buildings and houses, doing more than £300,000 worth of damage. Twelve people died, 102 were arrested, and 31 sentenced to death.

Because of the French Revolution (1830), and making the King nervous, William IV agreed to pack the House of Lords with some Whigs, so that when another Reform Bill passed the Commons, it could go on to pass the Lords, becoming the Reform Act of 1832.

1832 – Reform Act

The Reform Act 1832 (also known as the Representation of the People Act) was the first piece of legislation to expand voting rights in the United Kingdom, and saw 56 Rotten Boroughs disappearv, and 67 new constituencies created… although constituencies still weren’t of remotely even sizes. In the countryside, the franchise was extended to include small landowners, tenant farmers, and shopkeepers. In towns, men who paid a yearly rent of £10 or more could vote, along with some lodgers, even if they didn’t own the property but they could afford to rent someplace expensive enough, and they could be trusted to vote responsibly. This had the effect of Disenfranchisement: It excluded working class men (six men out of every seven), and for the first time, women were specifically excluded from the franchise. Before that, most women chose not to vote as a matter of custom – not law, though in a few instances women had voted.

1894 – The Local Government Act

The Local Government Act is passed, which allows married and single women to vote in elections for county and borough councils.

1897-1918 – The Suffragist Movement (NUWSS)

Lasted for 21 years

Accomplishments:

Affiliating with the Labour Party and enabled them to win; The Representation of the People Bill is passed, allowing women over the age of 30 and men over the age of 21 to vote; The Parliamentary Qualification of Women Act is passed, enabling women to stand as MPs; Qualification of Women Act is passed.

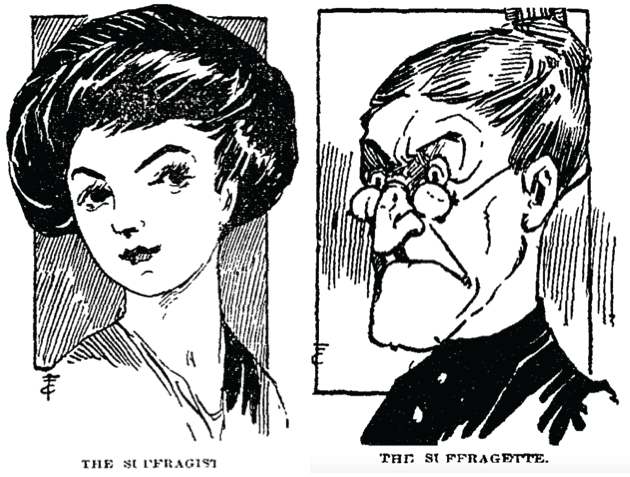

1897 – Millicent Fawcett, NUWSS (Suffragist Movement)

As a response to this new disenfranchisement, of all women and most men, several suffrage societies were created. And in 1897 Millicent Fawcett brought them all together, founding the NUWSSvi– the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies, aka what became known as the Suffragist Movement and what we would today call the first feminist movement: fighting for the suffrage of women and working-class men, based on equalityvii. By 1914 had over 50,000 membersviii.

Millicent Fawcett was born in 1847 and married the Liberal MP Henry Fawcett in 1867. She began a writing and speaking career – discussing women’s education and women’s suffrage, among other issues. After the death of Lydia Becker, Fawcett emerged as the suffrage movement’s leader and presided over a committee that eventually became the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) in 1897. Fawcett found support among middle-class and university women as well as working-class women who preferred the NUWSS’s peaceful, legal campaigning methods (rather than the middle-class focused Suffragette Movement’s violence). Fawcett recognised the positive effect of the First World War on the suffrage campaign and encouraged campaigners to accept the compromise of women over 30 being enfranchised. She resigned as president of the NUWSS in 1919 but was still heavily involved with the organisation, rechristened as the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC). She campaigned for the legal profession to be opened to women, for example. She died in 1929.

Suffragist Manifesto

The above copy of the Suffragist demands, to be met through peaceful means, was collected and preserved by Maud Arncliffe Sennett. Many of her remaining historical copies of posters, meetings, and news clippings can be found in the British library, where much of this essay derives its information.

Maud Arncliffe Sennett was born in 1862 and became interested in the women’s suffrage movement in 1906 when she read a letter by Millicent Fawcett in The Times. She was a member of both the NUWSS Suffragist Movement, and later the WSPU Suffragette Movement – though she left it to join the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) denouncing the militant Marxism of the WSPU (Suffragettes). Arncliffe Sennett documented the suffrage campaign in a series of scrapbooks (both Suffragist and Suffragette), and 37 volumes of her scrapbook were donated to the British Museum (and now belong to the British Library) by her husband after she died in 1936ix.

As well as belonging to both the NUWSS and the WSPU, Arncliffe Sennett also joined the Women’s Freedom League, and the Actresses’ Franchise League. She also founded, in July 1913, the Northern Men’s Federation for Women’s Suffrage. Arncliffe Sennett provided several thousand red and white rosettes for the NUWSS’ first large scale demonstration on 7 February 1907, known, because of the terrible weather conditions, as the ‘Mud March’.

Arncliffe Sennett was briefly imprisoned in Holloway prison in November 1911 for breaking the windows at the Daily Mail offices. Between 1906 and 1913 The NUWSS had worked tirelessly on a highly organised and politically strategic campaign to get successive governments to introduce votes for women, following their decision to do so within the law. As one historian has notedx, they were not seeking to overthrow the political establishment but, as respectable middle-class women, were “asking to be let in”.

1903 – In October, Emmeline Pankhurst sets up the ‘socialist version’ WSPU (Suffragette Movement), which chooses revolution through violence as its model, and begins active revolution. Up until this point, the Suffrage Movement had been deliberately apolitical, though the Pankhursts and others wanted to change the political system, as was being attempted around the world.

1905 – The Militant WSPU adopts the motto: “Deeds not Words”, resulting in the WSPU becoming even more violent, as seen in 1907.

1907 – In February, the NUWSS Suffragists organise the ‘Mud March’ where 40 Suffragist societies and, over 3000 women, marched from Hyde Park to Exeter Hall in the rain and mud; and in August, the Qualification of Woman Act is passed… and a fifth of the Suffragette WSPU membership abandon them, for their increasing violence, and instead join the WFL – Women’s Freedom Leaguexi. On the 8th of March, the Women’s Enfranchisement Bill (the ‘Dickinson Bill’) is introduced to Parliament for its Second Reading but fails, which prompts the WSPU Suffragettes to storm the Houses of Parliament and get arrested.

1908 June – Women’s Sunday: The remaining Suffragettes smash windows with stones, with written messages attached, in Downing Street and tie themselves to railings. Because of the effect of the small socialist violence group: WSPU was having against the Suffrage movement, the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (WASL) is formed (which in 1910 merges with the Men’s National League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage).

1909 – The Women’s Tax Resistance League (WTRL) is formed: a direct-action group who refused to pay taxes without political representation. Their founding slogan is ‘No vote, no tax’.

1911 – Instead of announcing a Universal Suffrage Bill as the NUWSS Suffragists had been lobbying for, Asquith announces a Manhood Suffrage bill, which is seen as a betrayal of the women’s suffrage campaign. In protest, the WSPU Suffragettes organise a mass window-smashing campaign through London. This heightened militancy by them continues into 1912, and spirals to include arson attacks.

1912 – The Labour Party become the first political party to include female suffrage in their manifesto. This was in reaction to the NUWSS’s ‘Election Fighting Fund’, which was set up to help organise the Labour campaign

1913 February – The WSPU Suffragettes step up their campaign to destroy property, including destroying Orchid house at Kew.

Unfortunately, the subsequent bills kept failing, so after the defeat of the third Conciliation Bill in March 1912, and the withdrawal of the subsequent Reform Bill in January 1913, the NUWSS had a ‘radical’ change of strategy: now they aimed to put pro-suffrage MPs in Parliament in time for the next general election, due in 1915. They did this by focusing on the parliamentary constituencies and the public. They created mass leafletsxii to raise awareness of the suffrage movement, and garner support from the working classes. In 1912 they formed an alliance with the Labour Party.

Another reason for the NUWSS’ sustained propaganda campaign was to distinguish themselves from the militant socialist WSPU of Emmeline Pankhurst who, in February 1913, stepped up their campaign to destroy property, including the smashing the orchid house at Kew.

The NUWSS Suffragists were concerned that the militant tactics of the WSPU Suffragettes would undermine their cause, and so they sought to present themselves as the respectable face of the suffrage campaign – note the words ‘law-abiding’ at the top of the leaflets: In the leaflet What does Women’s Suffrage Mean (B 100), the writer states, “some people think that Women’s Suffrage means breaking windows and spoiling other people’s property… [but] thousands of quiet law-abiding women are asking for the vote”.

They were keen to reassure the public that they did not want to challenge women’s role as mothers and homemakers. In their aim to win over working-class women, they set out to persuade them that they needed the vote to protect their interests as wives, mothers, and workers (this can be seen in the leaflets Votes for Mothers (B. 111), Women in the Home (B. 44) and Some Reasons Why Working Women Want the Vote (B. 23)). Although this argument went against the Suffragists’ liberal view that women were equal to men, it made the idea of suffrage more acceptable – and it therefore gained more supportxiii.

Moral reform was also of great interest to the NUWSS. One of the issues they campaigned on was so-called ‘White Slavery’, an Edwardian euphemism for forced prostitution and trafficking. In Parliament and Moral Reform (B. 106), the spotlight is on the sexual abuse of young girls. Without the female vote, the suffragists argued, there was ‘no “voting power” behind the demand for these reforms’ (B. 106r).

1918-1928 – Suffrage

1918 – The Representation of the People Bill passes, and Millicent Fawcett leaves the NUWSS, and it becomes the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship. The Bill didn’t go far enough into establishing the right to vote for all women as it still required them to own property to vote at age 21 instead of 30, but it did do away with the property requirements for men, giving the right to vote for all men aged 21, regardless of race or class.

1928 – The Representation of the People Act 1928 did away with the property requirements for women, finally opening the door to all persons 21 years of age or older.

1929 – General Election

All women aged 21 were able to vote in their first General Election, and Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour party takes over from the Conservatives.

1903-1914 – The Suffragette Movement (WPSU)

Lasted for 11 years

Accomplishments:

Re-writing history of suffrage to aid the narrative of victimisation of women at the hands of men, thus erasing the Suffragists’ achievements while taking credit for the new narrative, and becoming known by both contemporary pro- and anti-suffrage activists and supporters as ‘terrorists’ embarking on damaging ‘terrorism’ to create a One World Globalist Communist government and world.

1903 – Emmeline Pankhurst, WSPU (Suffragette Movement)

10 years after Millicent Fawcett (NUWSS) had brought together women to fight for equality of women’s and men’s rights, including the right to vote after legislation preventing working class men and all women had been passed, a new society emerged (that has come to have dominated our ‘history and understanding’ of the women’s movement) in the UK: the WSPU, or Women’s Social and Political Movement, created by the Pankhurst family. It subsequently had a turbulent career aside from its method of violence and attack on men, patriarchy, and the church, with the aim to establish a communist world. It had several internal rifts over its socialist model of governance: in particular the undemocratic authoritarian role of Emmeline Pankhurst as leader.

The WSPU adopted militant, direct action tactics: chaining themselves to railings, disrupting public meetings and damaging public property (similar to their contemporary Marxist and socialist movements around the world, as well as Antifa – then and now, and BLM tactics today). In 1913, Emily Davison stepped out in front of the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby. Her purpose remains unclear, but she was hit and later died from her injuries.

Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters: Christabel, Sylvia, and Adela are well-known names in Suffragette history, but necessarily not for their divergence from the suffrage movement because of their choice to turn to violence and extreme actions.

Today we would describe them as ‘terrorists’, but it is not just by today’s standards that their movement would be defined as suchxiv, as they were also defined thus by their suffrage contemporaries. For modern scholars, reattaching these facts runs the risk of accusations of patriarchy agency, and feminism bashing. It’s a serious flaw in the scholarship, and a prejudice that needs to be corrected.

The Pankhursts passionately believed that “deeds, not words”, would be the only thing to convince the government to give them the vote. After decades of peaceful protest, the WSPU decided that something far more drastic was needed to get the government to listen to those who were campaigning for women’s rights. While we are familiar with tactics such as window smashing, what was the real scale of suffragette violence and militancy?

1907 – WFL split from WSPU

Unhappy with Emmeline Pankhurst’s approach – particularly the advocacy of violent actions, and her undemocratic authoritarianism – a split occurred in the WSPU, leading to the formation of the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). Unlike the terrorism (sic) of the Suffragettes in the WSPU, the WFL favoured peaceful lawbreaking such as disruption, and refusal to pay taxes and complete the census (the NUWSS disagreed with all lawbreaking, especially including the census boycott which they believed would weaken their argument). Despite the clashes of opinion over tactics, the NUWSS, WSPU and WFL continued to work together on certain elements of the campaign, but varied greatly when it came to tactics and politics: and this is when these Suffragettes were ostracised due to what the other groups called “terrorism”, which is also how these actions should, and would, be seen today.

March 1907 – Dora Thewlis is gaoled

Dora Thewlis, a mill worker from Yorkshire, took part in the mission to break into the Houses of Parliament in March 1907. She was only 16 at the time, and newspapers became fascinated by her story and her arrest. Some

days after her arrest, it was reported, by the girl’s parents, that she had been brought up in an “atmosphere of socialism” and that they supported her actions, demanding that she received the same punishment as other suffragettes despite her agexv. Yet, in both court and the press, Dora was patronised, represented as an unknowing child ‘enticed’ from her home, and dubbed as the ‘baby suffragette’xvi.

1912 – The Suffragette paper is founded

Christabel Pankhurst edited ‘The Suffragette’, which was founded in 1912, and replaced ‘Votes for Women’ as the WSPU’s (Suffragette Movement) official voice. Its pages hosted a ramped-up militant tone, documenting stories of attacks on property and historic stories of belligerent action, and successes of socialist comrades abroad. The issue on Pankhurst’s desk (below) features an illustration of “the burning of Nottingham castle during the franchise agitation of 1832” – the content inside alludes to the use of arson, window-breaking and theft. Militant action was the WSPU Suffragette Movement’s contribution to the campaign for women’s suffrage.

Were the peers of Suffragettes correct to call them ‘terrorists’?

One of the main Third-Wave feminist arguments today against using ‘terrorism’, is that the Suffragettes didn’t kill anyone. This seems to be the fundamental issue for modern feminists who are more socialist than their predecessor Second-Wave, but just because no-one died, doesn’t mean an act of terrorism hasn’t been committed, as the UK law on terrorism statesxvii. Under this definition, the Suffragettes were indeed terrorists, and their peers were correct to call them so, and distance the suffrage movement from them.

But did the Suffragettes agree with this classification? It is best to go directly to Christabel Pankhurst, the Movement’s publicist, and editor of ‘The Suffragette’, who herself wrote in The Evening Telegraph (below). Here she makes the Suffragette message very clear – it is one designed to shock and intimidate the government, and those areas of society that did not allow her voice, and the voice of all women, to be heard. It was to advance the cause of the Socialist Suffrage Movement, it involved the threat of serious violence, damage to property, and endangered lives. But as this was in response to just one event, could it have been a one off? The answer to that is a categorical no…

One only needs to look at the ‘Suffragette Outrages’ reported in their contemporary press to quickly see that the scale and scope of Suffragette violence is far grander than scholars have ever seem to have realised, or admitted. Some scholars might argue that the reports were just sensationalised, dramatised to sell more papers and paint the Suffragettes as hormonal, hysterical monsters… but the reports also exist in the Parliamentary Papers, which includes lists of the “incendiary devices”, explosions, artwork destruction, arson attacks, window-breaking, postbox burning, and telegraph cable breaking that occurred during the most militant years from 1910-1914.

I won’t deny that biased reporting would have been rife, both pro- and anti-suffrage, but this doesn’t alter the facts of the case: A pipe bomb is still a pipe bomb, it doesn’t become less dangerous or less important just because it’s a woman who has set it.

To continually deny the Suffragette levels of suffrage violence, and the forms that it took is, I feel, patronising to those erased-from-history women whose power, passion, and political extremism, such as the Suffragists and WFL, who so dominated the debates on Women’s Right’s before the First World War, and who achieved such success despite the violence of the Suffragettes.

i HTTPS://WWW.BRITANNICA.COM/TOPIC/ROTTEN-BOROUGH

ii HTTPS://WWW.ENCYCLOPEDIA.COM/HISTORY/ENCYCLOPEDIAS-ALMANACS-TRANSCRIPTS-AND-MAPS/ROTTEN-BOROUGHS iii HTTPS://WWW.GUIDEOFENGLAND.COM/SALISBURY/OLD-SARUM-ROTTEN-BOROUGHS-SALISBURY.HTML

iv HTTP://WWW.NATIONALARCHIVES.GOV.UK/PATHWAYS/CITIZENSHIP/STRUGGLE_DEMOCRACY/GETTING_VOTE.HTM v HTTPS://WWW.PARLIAMENT.UK/ABOUT/LIVING

HERITAGE/EVOLUTIONOFPARLIAMENT/HOUSEOFCOMMONS/REFORMACTS/OVERVIEW/REFORMACT1832/

vi HTTPS://WWW.BL.UK/COLLECTION-ITEMS/~/LINK.ASPX?_ID=21E2AE955DBE46F398B8C8457D51B79C&_Z=Z vii HTTPS://WWW.BL.UK/COLLECTION-ITEMS/NUWSS-PAMPHLETS?SHELFITEMVIEWER=1

viii LESLIE PARKER HUME, THE NATIONAL UNION OF WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE SOCIETIES 1897-1914 (NEW YORK & LONDON: GARLAND PUBLISHING INC., 1982), PREFACE.

ix HTTPS://WWW.BL.UK/COLLECTION-ITEMS/MAUD-ARNCLIFFE-SENNETTS-SCRAPBOOK-VOLUME-1

x IBID PARKER HUME, P. 13.

xi JILL LIDDINGTON, REBEL GIRLS, (LONDON, 2006), P. 67.

xii HTTPS://WWW.BL.UK/COLLECTION-ITEMS/NUWSS-PAMPHLETS?SHELFITEMVIEWER=1

xiii IBID PARKER HUME, P. 194.

xiv HTTPS://VICEANDVIRTUEBLOG.WORDPRESS.COM/2013/06/06/SUFFRAGETTE-OUTRAGES-THE-TERRORIST-ARGUMENT/ xv THE DAILY CHRONICLE, ‘GIRL SUFFRAGISTS’, (25TH MARCH 1907), AS FOUND IN SUFFRAGIST MAUD ARNCLIFFE SENNETT’S SCRAPBOOK, VOLUME 1, P.50

xvi THE TIMES, ‘INFANT AGITATORS’, (MARCH 22ND 1907), AS FOUND IN SUFFRAGIST MAUD ARNCLIFFE SENNETT’S SCRAPBOOK, VOLUME 1, P.51 xvii HTTPS://WWW.LEGISLATION.GOV.UK/UKPGA/2000/11/SECTION/1